Improving the Breadfruit Drying Process

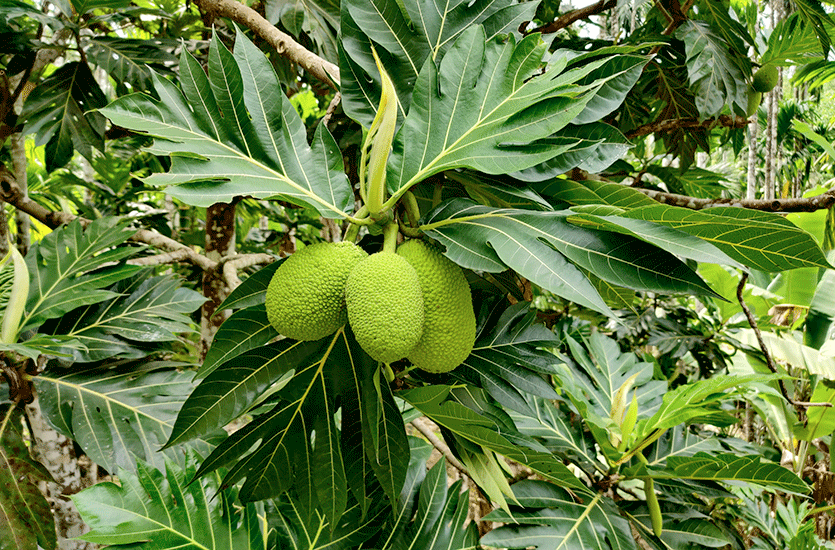

Breadfruit is an important culinary staple throughout much of the world, providing a nutritious substitute for wheat flour. But the fruit must be harvested then quickly peeled, dried, and refined before use — a time-consuming and potentially expensive process in developing countries.

For 15 years, the Trees That Feed Foundation has helped plant breadfruit trees and support fruit-harvesting equipment throughout the Caribbean and Africa. Years ago, with the help of Segal Design Institute students, the foundation created a solar dryer to speed up this refining process.

This year, the foundation returned to work with first-year Design Thinking and Communication students to see how the breadfruit drying and refining process could be improved.

“Every time we have worked with Northwestern students, we have been very happy with the creativity shown,” said Mike McLaughlin, cofounder of the Trees That Feed Foundation. “Every time they give us a nugget of something we haven’t thought about that we ultimately put into practice.”

The first-year students were up for the challenge — but first, they had to identify the problem. In fact, finding the right problem behind the perceived problem is one of the most important steps in the design thinking process.

"The students were overwhelmed at first,” said Shuwen Li, an associate professor of instruction of the Cook Family Writing Program in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences who cotaught the course. “They realized they needed to do primary and secondary research, then do some critical thinking to identify the problem.”

To find the right problem, students spent weeks researching the manufacturing process and interviewing users of the solar dryer. To connect with the users in the Caribbean and Africa, they used email, video calls, and text messages.

“They sent us photos of their dryer set-ups, and we talked over video calls,” said Joshua Hershey, a rising second year mechanical engineering student. The students, many of whom hadn’t ever traveled to these areas, got a better understanding of the day-to-day life of users, for whom breadfruit provides both a livelihood and community.

“They have completely different circumstances and day-to-day routines,” said Jonah Turner, a rising second year environmental engineering student. “It was a big mindset shift to have, but to be at a top university and use our education to give back to a community like this so early on was very important and a good opportunity to reflect on. It showed me how I can use my opportunities to help others.

Once the teams came up with their ideas, they went through a design review, where classmates questioned and critiqued potential designs. With new iterations, the teams hit the Prototyping and Fabrication Lab to bring their designs to life.

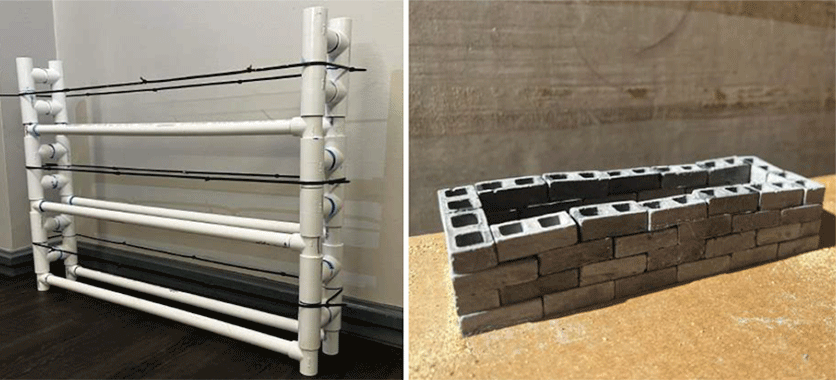

Ultimately, the teams developed four different ideas to improve the breadfruit drying process. Two teams focused on improving the trays used to hold breadfruit in the dryers. Users of the dryers had identified several problems with these trays, including debris falling onto the breadfruit, uneven drying of the fruit, and loss of product when the trays were unloaded from the dryer.

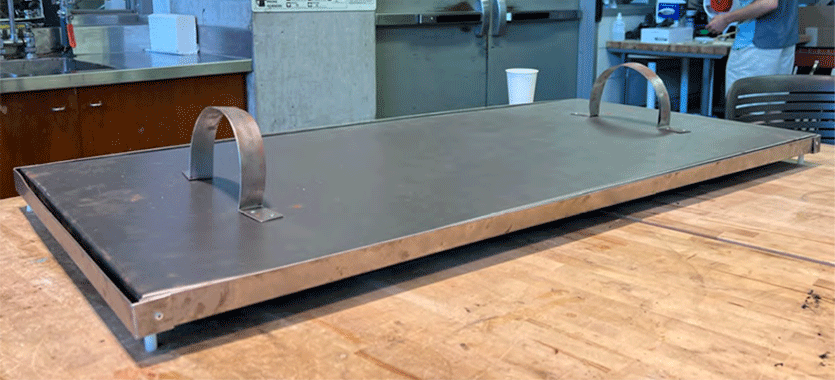

Hershey and his teammates designed the “MeshMate,” which contains five stacking trays made of stainless-steel mesh, all covered with a lid. The stacking allows for trays to be easily stored, while the lid prevents debris from falling in. The mesh allows for better air circulation.

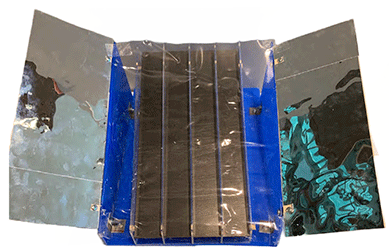

Turner’s team also focused on the tray design. Their “AirMesh” tray sandwiches fruit between two layers of food-grade mesh. With this design, the user can flip the tray over during the drying process, allowing for more evenly dried fruit.

Turner’s team also focused on the tray design. Their “AirMesh” tray sandwiches fruit between two layers of food-grade mesh. With this design, the user can flip the tray over during the drying process, allowing for more evenly dried fruit.

A third team added air channels and mirrors to the solar dryer, increasing the temperature of the air to make the breadfruit dry faster. A fourth team developed a separate “Refruiterator” made from cinderblocks that cools and prolongs the life of breadfruit after harvest.

“It’s always interesting to see how they make their decisions of what problem to pursue,” said Stacy Benjamin, a clinical professor in the Segal Design Institute who cotaught the course. “All four teams were presented with the same information, but they chose their designs based on what the users said. They did a good job managing that communication through language, time zone, and connectivity barriers. They were first years, but they jumped right in and did it.”

“All of their designs show solutions to real problems,” said McLaughlin, who is currently looking at how the foundation can implement the students’ ideas. “It’s work like this that helps feed people, that helps small businesses start up and succeed.”

“All of their designs show solutions to real problems,” said McLaughlin, who is currently looking at how the foundation can implement the students’ ideas. “It’s work like this that helps feed people, that helps small businesses start up and succeed.”

The students got their first taste of the design-thinking process, which they have already put into use. Hershey said he is already applying the process during his internship this summer. “I’ve been able to see just how useful design thinking is in my career, as well,” he said.