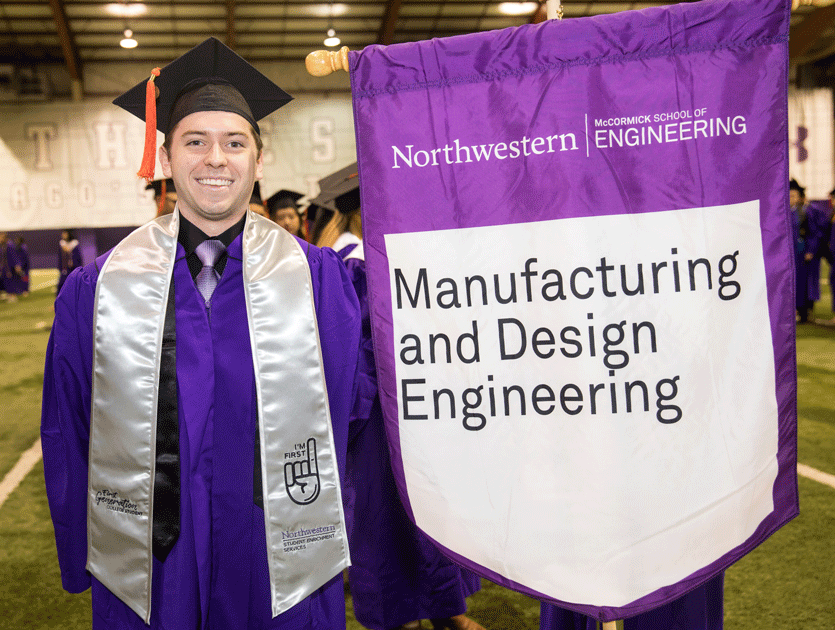

MaDE Celebrates its 20th Anniversary

Housed within the Segal Design Institute, the Manufacturing and Design Engineering degree program teaches students how to integrate design and manufacturing processes to bring a product to life.

As Charlotte, North Carolina, high schooler Kevin Kaspar whittled down his college list in 2019, he couldn’t ignore one distinctive Northwestern edge: the University’s bachelor of science degree in Manufacturing and Design Engineering (MaDE).

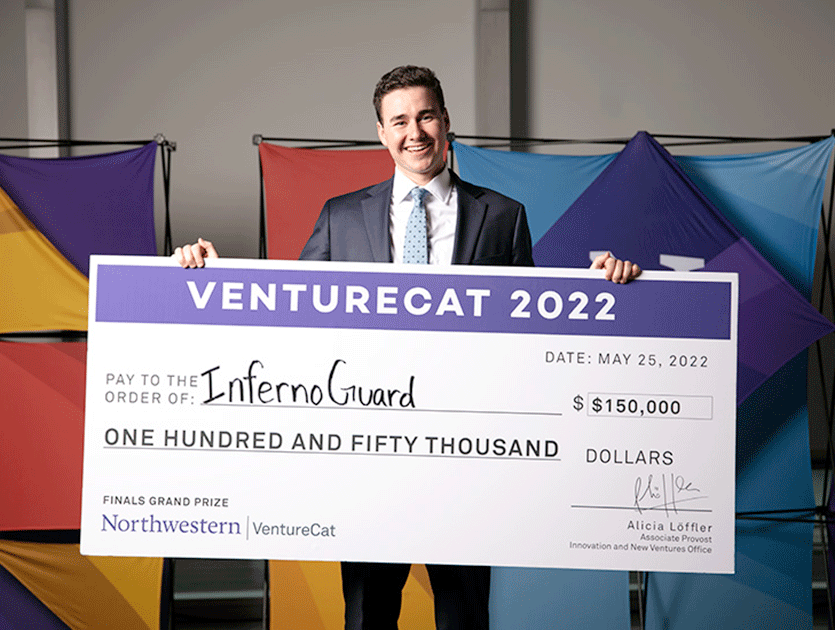

Having created a wildfire detection and warning system for landowners in fire-prone areas, Kaspar thought MaDE’s mix of engineering and creative principles would help him advance his product in more strategic ways. Over the last two-plus years for Kaspar, the MaDE program combined with Northwestern’s broader entrepreneurial ecosystem has delivered on that promise. In 2022, Kaspar and his wildfire detection startup InfernoGuard won the VentureCat grand prize.

“MaDE has provided critical knowledge on manufacturing processes and helped me understand how to better address user needs and work within the constraints of design to ensure a scalable solution,” said Kaspar, whose company, InfernoGuard, claimed the $150,000 VentureCat grand prize last spring.

Launched in 2002, when human-centered design was only beginning to pop up in academia, MaDE pioneered the idea of a design-centric degree at a top engineering school and celebrates its 20th year in 2022 as one of the nation’s few accredited manufacturing and design engineering programs – and the only one found at an elite Research I institution.

The making of MaDE

As the 21st century approached, Northwestern Engineering leadership began peppering human-centered design throughout the engineering curriculum, including the introduction of Design Thinking and Communication (formerly called Engineering Design and Communication), a cross-school course jointly taught by faculty from McCormick and the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences Cook Family Writing Program, challenging first-year students to create solutions to design problems for industry partners.

For students energized by that first-year course, however, there was nowhere else to turn for more intensive design-focused study. And so, they retreated to their traditional engineering studies and dabbled in human-centered design. Design was present, but far from fully explored.

At the same time, an existing undergraduate degree program called Manufacturing Engineering languished, graduating no more than 10 students annually throughout much of the 1990s.

Bruce Ankenman, then a young professor with a background in manufacturing, noted a compelling opportunity to marry an earnest study of design with elements of the existing Manufacturing Engineering curriculum, which touched distinct industries and carried wide-ranging practical considerations.

Bruce Ankenman, then a young professor with a background in manufacturing, noted a compelling opportunity to marry an earnest study of design with elements of the existing Manufacturing Engineering curriculum, which touched distinct industries and carried wide-ranging practical considerations.

“Design needed to be rooted in something and manufacturing was a fitting place,” Ankenman said. “You need to think about what humans will love, but also what you can make at quantity and at cost.”

In the fall of 2002, the McCormick School of Engineering debuted its design-focused major with a fitting name: MaDE. (Though Ankenman wanted to lead with design and call the new program Design and Manufacturing Engineering, he acknowledges MaDE was too perfect an acronym to ignore.)

In its opening years, MaDE grew steadily, positioning itself to both accept swelling student interest in design and propel Northwestern’s leadership in the nascent academic field. Students took classes in various departments, such as mechanical engineering and materials science, as well as courses at the Segal Design Institute, which opened in 2007 to champion human-centered design.

“We were giving students the skills and tools to develop and design relevant solutions so they could go into industry and contribute,” said Ankenman, the MaDE program’s founding director.

Building on MaDE’s foundation

In 2011, David Gatchell, clinical professor in the Segal Design Institute and mechanical engineering and biomedical engineering departments, replaced Ankenman as program director. While Ankenman spent the previous decade juggling MaDE with other responsibilities, Gatchell possessed the bandwidth to invest in recruiting and supporting students as the program’s full-time director.

“David ran with it,” Ankenman said. “He made it a club of people interested in design and a personal place where students felt connected and invested.”

In 2004, MaDE graduated two students, both double majors. By 2019, the program regularly boasted upwards of 35 graduates each year. The swelling student count spurred the addition of faculty members and classes, including a three quarters-long capstone project in which final-year students research an unmet need and develop a product. Last year, all five teams in that course filed provisional patents for their products.

MaDE students leave with a versatile degree they can bring into a diverse array of fields. Some go to established entities such as Boeing or Tesla while others work in smaller organizations, from boutique consulting groups to startups developing apps or services.

“We encourage students to find their voice within the program and capture the vast opportunities before them, especially given the demand for human-centered designers these days,” Gatchell said.

Over the last two decades, Gatchell said MaDE has “stayed true to its roots as a human-centered design major” while also evolving to reflect student desires and industry needs. The program has remained at the cutting-edge of manufacturing and assembly, incorporated skills applicable to ascendant fields such as digital design and human-computer interfaces, and sharpened its focus on entrepreneurship allowing students to pursue compelling commercialization opportunities.

“We see more and more schools try to emulate what we’re doing at Northwestern,” Gatchell said. “It’s flattering, but also a reminder we need to continue elevating our game so MaDE remains something special and singular.”